A bunch of outlets have published “State House Races to Watch” lists (Star Tribune, Minnpost, Minnesota Reformer). These are interesting, but they don’t tell you who is going to win. I’m not going to do that either, but I did put together a model that makes some predictions. The model incorporates the past voting history in each district, expectations about how much change we might expect to see in that past voting behavior, and some digging into the specifics of each swing race.

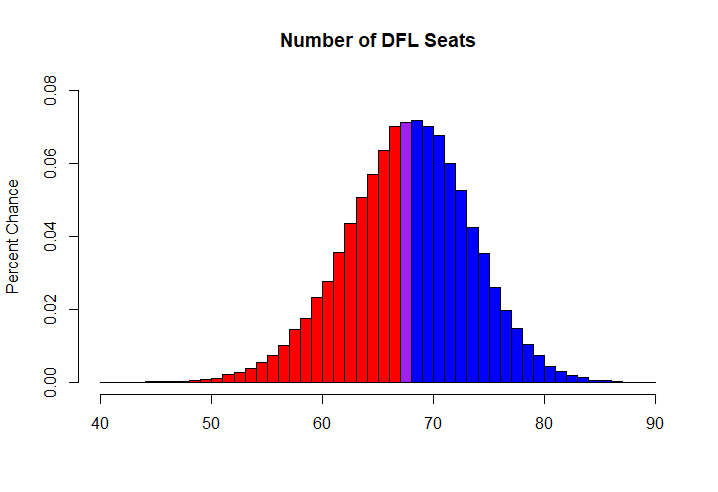

According to this model, The DFL is a very slight favorite to retain control of the State House. Specifically, I estimate that DFL has a 56 percent chance to retain control of the State House, while the Republicans have a 37 percent chance of winning control, and there is a 7 percent chance of a 67-67 tie. The election is likely to be very close - the most likely outcome is a 68-66 split in favor of the DFL, but a 67-67 tie is the second most likely.

This slight DFL advantage is largely the result of DFL strength in retaining incumbents, recruiting quality candidates, and raising money. An important thing to remember: Despite Minnesota being a slightly blue-tinged state, the map is tilted slightly in favor of the Republicans, such that the median state House seat is 2.7 percent more Republican than the state as a whole.1 So a DFL advantage here is not the default - the Republicans will win back the State House someday - possibly even this November. But the DFL has an edge.

Still incumbency, candidate quality, and money will only get your so far in a highly-polarized age, and the DFL’s majority will depend on winning all of the “Lean” and “Likely” DFL seats and at least two of the six five that I’ve rated as “toss-ups.”

Where did these predictions come from? There are details on the method below. But first, the district-by-district ratings. The DFL starts with 55 safe seats and the Republicans with 53,2 so the DFL needs to win 13 of these seats to gain control and the Republicans 15. If the Republicans win 14 and the DFL wins 12, we get an evenly divided House and a power-sharing-agreement fight.

What the Table Says

The different rating categories mean the following

Toss-up: Both parties have between a 60% and 40% chance of winning.

Lean: Leaned-towards party has between a 60% and 75% chance of winning.

Likely: Likely party has between a 75% and 95% chance of winning.

Safe seats are those that one party has more than a 95% chance of winning.3

In addition to the ratings, the fundraising totals report the amount raised in 2024 and the total cash-on-hand as of the primary election.4 The “Inc” column shows whether there’s an incumbent running and of which part (“O” means an open seat).

The “Chance of Being Pivotal” column is a little more complicated. As described below, the race ratings are based on simulating the House election 100,000 times. In 20,466 of these simulations (basically, one out of five simulations), control of the House is determined by a single seat - that is, the chamber is split 68 DFL/66 R, 68R/66 DFL, or 67-67. The chance of being pivotal is percent of these 20,466 simulations that the seat in question is the one that determined which party wins a majority or, in the case of a tie, which race has the closest margin.5

So Why Is the DFL Favored?

Two key thing stand out in the chart.

Incumbents: The DFL has incumbents running in enough districts to tie control of the chamber. There were three DFL retirements in non-safe seats, Gene Pelowski’s Winona-based 26A, Jerry Newton’s Coon Rapids based 35B, and Dave Lislegard’s 7B in the Iron Range. The Republicans have three non-safe-seat retirements. Two are toss-ups and, delightfully, these are the two East Metro districts that make up State Senate District 41, which famously gave the DFL its razor-thin Senate majority after 2022 by 321 votes.

Money: The DFL has a big cash advantage. The average DFL candidate has about 50% more cash on hand as the average Republican in these 26 races. In five key lean-D or toss-up races the Republican has less than $10,000 on-had (as of the pre-primary deadline). Money isn’t everything, but in low-salience elections like this one it can make a difference at the margins.

Two things are little less obvious:

Candidate Quality: There’s a big gap in candidate recruitment between the DFL and the Republicans. All of the lean-D seats feature DFL incumbents facing challengers who have never held office before and who have raised very little money. Two of the toss-up races (14B, 35B) also feature relatively inexperienced Republicans against more experienced DFLers who have raised much more money. Even with DFL incumbents, all of these races could be toss-ups or even Lean-R races, but the disparity in candidate quality nudges them towards the DFL. If the DFL wins a majority by winning all of these races, then whoever was running candidate recruitment for the Republicans has some questions to answer.

Geography: This conclusion doesn’t stand out unless you know Minnesota’s numbering conventions for legislative districts - basically, districts numbered in the 30s and above are in the metro, while those 30 and below are in greater Minnesota.6 The DFL can win a majority by winning the non-safe Metro-area districts; The Republicans will need to win at least two non-safe metro-area districts to get a majority.7 The DFL has good shot at some non-Metro districts, but they don’t need to win these districts, provided they can win the metro-area toss-ups. Notably, two of the three DFL retirements (7B and 26A) are non-Metro seats where the Republican candidate is now favored - if the DFL loses those, they might not win them again for a long time.

I think this last point is worth lingering on for a moment. The story of Minnesota politics over the last decade has been sharp and increasing geographic polarization. The old DFL coalition combined (as the party’s name suggests) Democrats in the urban core, Farmers in the south and northwest of the state, and Laborers on the Iron Range. Republican held seats in the Metro suburbs and central Minnesota. Now, the DFL is winning with the metro and a few seats in the state’s other urban areas, while a Republican majority hinges on holding onto a few exurban seats so that they aren’t completely swept out of the Metro suburbs.

Given the general trend of the Metro towards the DFL, this probably favors a DFL victory. But this would be a very different DFL than the DFL trifecta from a decade (2013-2014).

I’ll write up some more about the key races over the next few weeks. In the meantime, its gonna be a close one. It’s a useful reminder that the DFL trifecta that delivered the Minnesota Miracle 2.0 (and quite possibly Vice-President Tim Walz) was based on a very narrow legislative majority. 321 voters in State Senate district 41 gave the DFL a Senate majority in 2022. Those same voters could easily decide whether the DFL will retain its house Majority in 2024.

Wait, How Did you Calculate These Ratings? (AKA Methodology - Wonky Section Ahead)

This forecast has four steps. First, I estimate the partisan lean of each district. Second, I guess how much more Democratic or Republican the statewide political environment will be compared to 2022, as well as how uncertain I am about that guess. Third, I estimate how much more Democratic or Republican each district is likely to be given the specific candidates running in that race, as well as how uncertain I am about that guess.

Fourth, I simulate the election 100,000 times. In each simulation, I randomly draw a number to represent the overall shift in political environment, and randomly draw 134 numbers to represent the district-specific variation, with all these numbers drawn so that the average draw is the guess I made in steps 2 and 3, and the variation around that average informed by how accurate I expect each of these guesses to be. For each district, in each simulation, the computer adds together the partisan lean of the district, the overall shift in the political environment, and the district specific variation, to determine who wins that district in that simulation.

Adding up the winners across all districts determines who wins the House in that simulation, and adding up the winning party across all simulations gives me the percent chance each party has of controlling the House. Adding up the winners of one district across all simulations gives me each party’s chance of winning that district, and thus the district’s rating.

Some details on each step and reasoning behind the assumptions that I’m making:

Step 1: How Red or Blue is Each District?

I start by calculating the percent of the vote we’d expect a generic DFL candidate to get when running against a generic Republican candidate in a political environment that mirrors 2022. Political scientists refer to this as the district’s “normal vote.” Generally, this is calculated using results from past Presidential and statewide elections.

In this case, I use the 2016 and 2020 Presidential elections and the 2022 State Auditor race. Why the State Auditor race? Most voters don’t know who the State Auditor is so when they get to “State Auditor” on their ballot their only real cue is the partisanship of the candidates.8

Each district’s normal vote is the average of the percent of votes the DFL candidate received in that district,9 calculated to give the 2016 Presidential election half of the weight of the other two. I adjust this slightly so that the state-wide normal vote across all districts is the same as the statewide vote for the State House in 2022. In each district, this is the percent of the vote we’d expect the DFL candidate to get if voters were voting purely on party lines and IF the overall political environment was the same as 2022.

Step 2: How Democratic or Republican Leaning is the Political Environment?

Some years the electorate leans towards the Democrats, some years towards the Republicans. Generally, the change from one election to the next is very similar across districts - it is rare, though not unheard of, for a party to do better in one part of the state (or nation) and worse in another. We call this the “uniform shift” - how much will the electorate shift on average from how it voted in the previous election?

I expect to see a 0.25 point swing towards the DFL this year - that is, almost no change. There are good arguments for expecting 2024 to be a better year for the DFL than 2022; there are also good arguments for expecting 2024 to be a better year for the Republicans. Roughly, this was the back and forth in my head:

The country as a whole is likely to be more Democratic in 2024. In 2022, the aggregate vote for the US House was R + 1.6, a 3.7 point swing towards the Republicans from 2020. Right now, the generic ballot, our best tool for predicting the aggregate US House vote, is D + 2.2, implying a 3.8 point swing back to the Democrats, essentially replicating 2020.

BUT, Minnesota had almost no swing towards the Republicans in 2022 (R + 0.1). Since the DFL did not lose many votes between 2020 and 2022, they have less to gain. If we interpret today’s generic ballot as saying “this will be basically the same as 2020,” then we’d expect Minnesota to see no swing towards ether party.

The DFL and associated committees have a lot more money than the Republicans and associated committees. The DFL House Caucus has raised $5.5 million this year, compared to $1.8 million for the House Republican Campaign Committee. The State DFL has raised $5.9 million, the Republican Part of Minnesota only $300,000.

Tim Walz! Surely having a Minnesotan on the Democratic Presidential Ticket will help DFL State House candidate.

BUT, right now Harris/Walz is forecasted to do slightly worse in Minnesota than Biden/Harris did in 2020.

The big DFL legislative wins in the latest legislative session probably portend a swing away from the DFL. We refer to this as “thermostatic voting” - basically, we tend to see a swing away from the party in power, especially when that party does a lot of stuff, because swing voters get a sense that policy has moved too far in one direction. The most famous example of this is the Presidential midterm curse, in which the President’s party almost always loses seats in the midterm election.

I suspect this last point will draw the most objections, at least from DFLers. Partisans often assume that when their party passes a bunch of legislation, people will reward them in the next election. History suggests otherwise.

Overall, I think that these factors largely balance each other out, with a slight edge to the DFL from Walz coattails. But the model acknowledges that this is hard to predict - for each simulated election, it draws a random “uniform swing” and adds this to the normal vote in each district. On average, these random draws are DFL + 0.25 - but each individual draw deviates from this by an average of 1.92 points (i.e. from R + 1.67 to D + 2.17).10 In 46% of simulations, there is a swing towards the Republicans.

Step 3: What is the Effect of District-Specific Factors?

So far, we’ve generated a prediction for each district that is the DFL normal vote in that district plus the uniform swing. But, each contest will have some idiosyncratic factors - scandals, local issues, particularly strong or weak candidates, rain on your election day - that affect how it votes. These don’t matter a lot. The correlation between the district’s normal vote and its vote in state legislative elections is extremely high. But in close races, these things can make a difference.

These predictions incorporate district-level factors in two ways. First, each simulation draws a random district-specific swing and adds this to the sum of the district’s normal vote and the uniform swing. The average district-specific swing moves the expected vote 2.4 points towards one candidate or the other; this swing is equally likely to favor the Republican and the Democratic candidate.11 This adds uncertainty to the model at the district level, meaning that in each simulation some R-leaning districts will see a DFL upset and some DFL-leaning districts will see an Republican upset.

Second, in non-safe races I’m drawing on knowledge about each race and adjusting the expected vote share by a little bit. Primarily, I’m looking for the following factors:

Is an incumbent running? If so, how did they perform in the last election, relative to expectations? How active do they seem to have been while in office?

For non-incumbent candidate, have they previously held elected office?

How much money has each candidate raised? Is there an imbalance in fundraising?

Does either candidate seem to be ideologically out-of-step with the district?

Have there been any notable news stories or scandals?

Based on these, I’ll shift the expected vote towards one candidate or the other by a few points. The average adjustment is small, 1.5 points in one direction or the other.12

Step 4: Simulate 100,000 Elections

Finally, I simulate 100,000 elections, recording the outcome for each seat in each election as well as the number of seats won by each party. “Simulate an Election” sounds grand, but it just means drawing 135 random numbers: One for the uniform swing, which is added to all districts, and one district-specific swing for each district. I add these to the normal vote in each district, add any adjustment based on my knowledge of the race, and declare a winner.

To illustrate, let’s walk through these steps in district 32B, a Blaine-area district which has a relatively high chance of being the pivotal district:

The normal DFL vote in 32B is 49.1, meaning that it leans ever-so-slightly R.

But the district has a Democratic incumbent, Matt Norris, who beat a Republican incumbent in 2022 by a 51.1-48.9 margin. Norris has raised a whole bunch of money. His opponent, Alex Moe, is a law student who appears to have recently moved to the district (Moe ran for a Duluth-area Senate seat in 2022), Moe has roughly 1/10th the cash that Norris has. So, I add 2.5 points to the expected DFL vote, putting Norris at an expected vote-share of 51.6.

In the first simulation, the computer draws a uniform swing of DFL + 1.4. Maybe Walz-mania strikes. Norris is now up to 53 percent of the vote. The computer then draws a district-specific swing of R + 1.2. Maybe Moe ends up being a better candidate than I expect. But it isn’t enough, and Norris with 51.8 percent of the vote.

So far, so good for simulated Matt Norris. But fast-forward to the seventh simulation and everything goes wrong. The computer draws a uniform swing of R + 1.7, putting Norris at 49.8 - maybe there’s a substantial backlash to the Minnesota Miracle 2.0 legislative session. The computer draws a district-specific swing of R + 3.5 - maybe Norris’s campaign implodes or there’s some scandal. It adds up to Norris getting 46.3 percent of the vote. Simulated Matt Norris returns to simulated Blaine in disgrace.13

This is mostly the result of DFL votes being concentrated into dense urban areas. There are 14 districts where I’d expect the DFL to get more than 80 percent of the vote – there are no districts where I’d expect Republicans to get 80 percent of the vote

The Republican safe seats are: 1A, 1B, 2B, 4B, 5A, 5B, 6A, 6B, 7A, 9A, 9B, 10A, 10B, 11B, 12A, 12B, 13A, 13B, 15A, 15B, 16A, 16B, 17A, 17B, 19A, 19B, 20A, 20B, 21A, 21B, 22A, 22B, 23A, 23B, 24A, 26B, 27A, 27B, 28A, 28B, 29A, 29B, 30A, 30B, 31A, 31B, 32A, 33A, 34A, 37A, 48A, 54B, 57A, and 58B.

The DFL safe seats are: 4A, 8A, 8B, 18B, 24B, 25A, 25B, 34B, 36B, 38A, 38B, 39A, 39B, 40A, 40B, 42A, 42B, 43A, 43B, 44A, 44B, 45B, 46A, 46B, 47A, 47B, 49A, 49B, 50A, 50B, 51A, 51B, 52A, 52B, 53A, 53B, 55B, 56A, 59A, 59B, 60A, 60B, 61A, 61B, 62A, 62B, 63A, 63B, 64A, 64B, 65A, 65B, 66A, 66B, 67A, and 67B.

See above.

These are the fundraising numbers as of July 22nd, the end of the pre-primary reporting period. Unfortunately, Minnesota doesn’t require candidates to report donations and spending between the primary and the Oct 28th pre-General Election report, so we’re flying a bit blind here in evaluating how much money each candidate has.

This is the closest race won by the majority party or, in the case of a 67-67 split, the closest race overall. So, for example, at a six percent chance of being pivotal, Blaine’s district 32B is the contest most likely to determine control of the House conditional on the House being tied or one party having a one-seat advantage.

Single-digit districts are in Northern Minnesota, districts in the teens are in Central and Southern Minnesota, 20s are (mostly) districts in the South, and districts in the 30s-60s are in the metro, with districts in the 60s in Minneapolis or St. Paul.

The DFL has a handful of safe districts outside the metro in Moorhead (4A), Duluth (8A and 8B), Mankato (18B), and Rochester (24B, 25A, and 25B). Republicans has a smattering of safe seats on the exurban edge of the metro.

In some cases, the Attorney General or the Secretary of State would serve the same purpose, but Keith Ellison and Steve Simon get enough media coverage that some voters likely voted based on the candidates, not just the party. The only recent news coverage I’ve seen of Julie Blaha (who I am sure does a wonderful job) is for her seed art.

Technically, the percent of the 2-party vote. That is, the percent of the vote once votes for minor party, independent, and write-in candidates are removed.

In technical terms, each simulation’s swing is a draw from a normal distribution with mean of .025 and a standard deviation of .024. The standard deviation is derived from the average predictive accuracy of the generic ballot.

Again, in technical terms, each district-level swing is a draw from a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of .03. The standard deviation is derived from the average deviation from the normal vote of state house races in past Presidential-election years.

The largest adjustment is 3 points in favor of Zach Stephenson in district 35A. This is a district that really should be a toss-up, and the fact that it isn’t is a good illustration of why the Republican Party is not favored overall. 35A voted for Trump by 5 points in 2016, Biden by 4 points in 2020, and the Republican State Auditor candidate by 1 point in 2022. The DFL has a very active incumbent with a ton of money, the Republicans have a first-time candidate who has never held elected office and has raised very little money. Stephenson could still easily lose, particularly if it ends up being a Republican-leaning year instead of a basically neutral year. Still, it’s an indictment of Republican candidate-recruitment efforts that they couldn’t find some city council or school board member to run - or at least a rich person who’d self-fund their campaign.

Worth noting that this is an unusually bad outcome for Norris - he gets more votes than this in 90 percent of simulations and a better district-specific draw in 83 percent of simulations.